Cyrus Dallin

SCULPTOR

Cyrus Edwin Dallin

Studied At/With

Truman H. Bartlett, Boston ;

Academie Julian, Henri Michel

Chapu, Paris;

Ecole des Beaux Arts

BORN

22 November 1861, Springville, Utah

DIED

14 November 1944, Arlington, Massachusetts

“We can only create in life what we are and what we think.”

Cyrus Dallin

Birth and Early Life

Cyrus Dallin’s grandparents had moved to Utah after joining the Church. His parents had settled in the small Utah town of Springville, near where Dallin’s father mined. Despite the grandparent’s membership in the church, Cyrus’s parents Left the Church and did not raise their family in the faith.

Dallin grew up associating with the children in local Native American tribes. He first attempted sculpting by making animals that roamed the area, and busts of the local Indian leaders and chiefs out of river clay.[1]Knapp, Alma J, “The History of Cyrus Edwin Dallin, Eminent Utah Sculptor,”Thesis, University of Utah, 1948, p. 11. It was while working in his father’s mine that Dallin’s skills gained him recognition. A vein of white clay was discovered in the mine, and from it Dallin sculpted busts of a man and a woman.[2]Craven, Wayne, “Cyrus Dallin: American Sculptor 1860-1943,” University of Delaware via Harvardsquarelibrary.org, Accessed 04 March 2012. These busts were noticed by many regionally, and eventually gained him the attention of wealthy individuals who proposed to help him, like a prospecting visitor from Boston, C. H. Blanchard.[3]Knapp, p. 14.

Education

Blanchard encouraged Cyrus to study sculpture in a more formal setting. Blanchard sponsored him to attend the Bartlett Art School in Boston in 1880.

Most famously, Dallin is known for his statues of Paul Revere, created

for a competition for the city of Boston. Having had some artistic differences with his teacher, [4]“The Cyrus Dallin Story,” NortheastFineArts.com, accessed 5 June 2015. he had stared a small studio of his own in the city, and when the occasion arose he entered a competition to create an equestrian statue of Paul Revere.[5] Knapp, p. 15. He won the competition, twice, through an anonymous submittal process.

The Revere competition never really ended for Dallin, however. Despite winning, he had 6 versions of the statue rejected over a 58 year period before finally seeing his final submission cast and placed in 1940.[6]

“Dallin, Cyrus Edwin,” Springville Museum of Art. Accessed 30 September 2011. Much of the difficulty in getting his statue built can be attributed to the poor behavior of other sculptors, including his former instructor, Thomas Bartlett, who did all they could to turn public opinion against him for being a “mere youth hailing from the Godless west.”[7]“The Cyrus Dallin Story,” NortheastFineArts.com, accessed 5 June 2015.

Thanks to the help of a sympathetic Bostonian,[8]Knapp, p. 17. Dallin moved to Paris in 1888 to study at the Julian Academy.[9]“Dallin, Cyrus Edwin,” Springville Museum of Art. Accessed 30 September 2011. There he would model his first major work, a full size statue of a mounted Indian titled Signal of Peace. This first major sculpture for Dallin would also be the first to bring him international attention and an honorable mention from the Paris Salon.[10]Rell G. Francis, “Cyrus Edwin Dallin,” Utah History Encyclopedia, media.utah.edu. Accessed 10 January 2012.

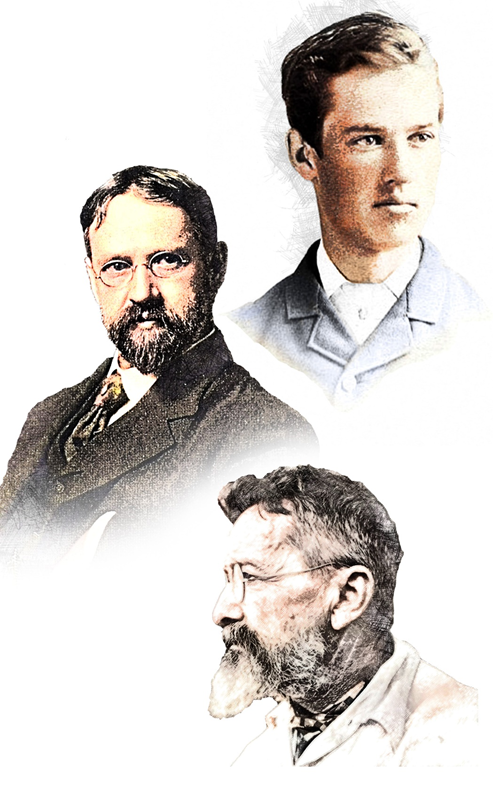

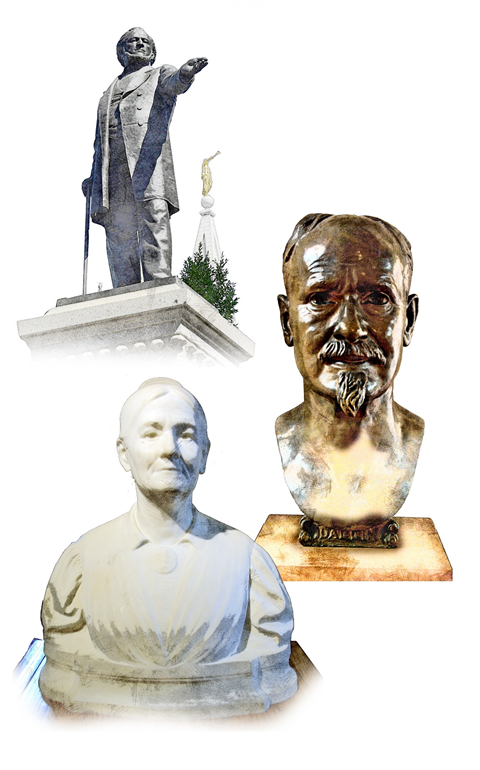

(Top) Paul Revere, 1899, Boston, Massachusetts; (Middle) Sir Isaac Newton, 1895, Library of Congress, Washington, DC; (Bottom) Wilford Woodruff, 1891, Salt Lake City, Utah, Conference Center. This is the bust Dallin carved that convinced Woodruff to request he sculpt the Moroni

Marriage and Return to Utah

Dallin would return to Boston in 1890, [11]Knapp, p. 22. where he married Vittoria Colonna Murray the following year.[12]Rell G. Francis, “Cyrus Edwin Dallin,” Utah History Encyclopedia, media.utah.edu. Accessed 10 January 2012. ] From there Dallin and his new bride returned to Utah.

It was on this return in 1891 that the now 30 year old Dallin was asked to sculpt a statue for the temple.[13]Florence S. and Jack Sears, “How We Got The Angel Moroni Statue,” Instructor 88 (October 1953): 292 He had gained international recognition by this point, and President Woodruff referred to him as ‘the great Modelist of Utah.”[14]

Wilford Woodruff journals and papers, 1828-1898; Wilford Woodruff Journals, 1833-1898; Wilford Woodruff journal, 1886 January-1892 December; Church History Library, (accessed: August 12, 2019) 13 July 1891. Having been impressed with Dallin’s work, he asked Cyrus to sculpt the Angel for the temple. The Salt Lake Temple was the first to have a statue specifically identified as the Angel Moroni.

Dallin would also be commissioned to create the Monument to Brigham Young. This is the monument that currently stands at the south end of the Temple Square Plaza.

Dallin and his wife returned to Paris for three years to study at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in 1895. [15] Knapp, p. 23.

Educator

Dallin found the life of a sculptor to be rocky. While his works one praise far and wide, making a living as a sculptor proved difficult. To support his wife and three sons he became a professor of Art, teaching primarily for the Massachusetts Normal Art School (Massachusetts College of Art and Design) for 41 years.[16]Craven, Wayne, “Cyrus Dallin: American Sculptor 1860-1943,” University of Delaware via Harvardsquarelibrary.org, Accessed 04 March 2012.

Other Pursuits

Sculpture was not the only interest Cyrus Dallin had. He had a great fondness for archery that led him to compete in the sport. He earned a Bronze Medal in the 1914 Olympics in St. Louis Missouri for team archery.[17]”Archery – Cyrus Edwin Dallin (United States) : season totals“. The-sports.org. 1904-09-21. Retrieved 2012-02-12.

Religion

Though being raised by his parents as a student in a Presbyterian School[18]

Albert L. Zobell, Jr, “Cyrus Dallin and the Angel Moroni Statue,” Improvement Era 72 (April 1968) p. 5. , in a Latter-day Saint community, Dallin would eventually choose to become a Unitarian. This makes him unique among all the current sculptors of an Angel Moroni statue, in that he is the only one never to have joined the Church

Museum

Dallin is an internationally recognized sculptor. A museum in his honor exists in Arlington Massachusetts in the historic Jefferson Cutter House.[19]

“The Cyrus E. Dallin Art Museum“. dallin.org. Retrieved 2014-07-28. Additionally the home he bought for his parents in Springville, Utah is on the National Historic Register.[20]

“Dallin House,” Wikipedia.

“The events of my youth are my dearest possessions.

I have received two college degrees: Master of Art, and Doctor of Art, besides

medals galore, but my greatest honor of all is, ‘I came from Springville,

Utah.'”

-Cyrus Dallin

Famous Works by Cyrus Dallin

| “Signal of Peace” | Lincoln Park, Chicago, Illinois | 1890 |

| “Angel Moroni” | Salt Lake Temple | 1891 |

| “Brigham Young and Pioneers” | Salt Lake City, Utah | 1891 |

| “Medicine Man” | Fairmont Park, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | 1899 |

| “Appeal to the Great Spirit” | Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mass. | 1909 |

| “Gen. Winfield S. Hancock” | Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania | 1913 |

| “On the Warpath” | Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina | 1914 |

| “Gov. William Bradford” | Pilgrim Hall, Plymouth, Massachusetts | 1920 |

| “Massasoit” | Cole Hill, Plymouth, Massachusetts | 1920 |

| “Chief Geronimo” | Donce Estate, Madison, New Jersey | 1926 |

| “Eli Whitney” | Rocky Creek, Georgia | 1928 |

| “Last Arrow” | Muncie, Indiana | 1929 |

| “Pioneer Mother” | Springville Art Museum, Utah | 1931 |

| “Paul Revere” | Paul Revere Hall, Boston, Massachusetts | 1940 |

Chapter 4 Navigation

Related Articles

References

| ↑1 | Knapp, Alma J, “The History of Cyrus Edwin Dallin, Eminent Utah Sculptor,”Thesis, University of Utah, 1948, p. 11. |

|---|---|

| ↑2, ↑16 | Craven, Wayne, “Cyrus Dallin: American Sculptor 1860-1943,” University of Delaware via Harvardsquarelibrary.org, Accessed 04 March 2012. |

| ↑3 | Knapp, p. 14. |

| ↑4, ↑7 | “The Cyrus Dallin Story,” NortheastFineArts.com, accessed 5 June 2015. |

| ↑5 | Knapp, p. 15. |

| ↑6 | “Dallin, Cyrus Edwin,” Springville Museum of Art. Accessed 30 September 2011. |

| ↑8 | Knapp, p. 17. |

| ↑9 | “Dallin, Cyrus Edwin,” Springville Museum of Art. Accessed 30 September 2011. |

| ↑10, ↑12 | Rell G. Francis, “Cyrus Edwin Dallin,” Utah History Encyclopedia, media.utah.edu. Accessed 10 January 2012. |

| ↑11 | Knapp, p. 22. |

| ↑13 | Florence S. and Jack Sears, “How We Got The Angel Moroni Statue,” Instructor 88 (October 1953): 292 |

| ↑14 | Wilford Woodruff journals and papers, 1828-1898; Wilford Woodruff Journals, 1833-1898; Wilford Woodruff journal, 1886 January-1892 December; Church History Library, (accessed: August 12, 2019) 13 July 1891. |

| ↑15 | Knapp, p. 23. |

| ↑17 | ”Archery – Cyrus Edwin Dallin (United States) : season totals“. The-sports.org. 1904-09-21. Retrieved 2012-02-12. |

| ↑18 | Albert L. Zobell, Jr, “Cyrus Dallin and the Angel Moroni Statue,” Improvement Era 72 (April 1968) p. 5. |

| ↑19 | “The Cyrus E. Dallin Art Museum“. dallin.org. Retrieved 2014-07-28. |

| ↑20 | “Dallin House,” Wikipedia. |

Last updated on: 29 October 2024